Num. 6 - October 2015

Tutti gli articoli

Tutti gli articoli

02 October 2015 Bandidos

For trying to understand the phenomenon of banditry in Sardinia in the 1800s, it is necessary to start with a historic consideration, as obvious and well known as essential: Sardinia suffered a bewildering series of dominations. Alberto Lamarmora in the book Voyage en Sardaigne wrote: “Whichever other population that, for many centuries, had found these negative circumstances like those that encumber on this Region, would not have been either so patient or so docile”.

With no doubts, at the base of this phenomenon, there is the condition of epochal mistreatment suffered by Sardinian citizens, intensified enormously in the 1800s. A quick historic excursus is important to clarify better the analysis. Beginning from the process of Roman domination of the Island that, in the Barbagia – the inside mountainous area – was not a true subjection. The Barbagia personifies mountain, it is the shelter of freedom, an Island into the Island that has not the sea as a limit, but other land.

The Roman domination of the Barbagia gave as heritage not only a big archaeological patrimony, but a significant mark on the language – the language spoken in the Barbagia, called "barbaricino", is the language with which the Latin language persists in a way that is clearer than other Romance languages of Europe. Romans before and Christianity then, spread slowly with other populations "come from the sea": Vandals, Byzantines, Pisa people, Aragon people, Spanish, Piedmonteses. For the populations of the hinterland and above all of the Barbagia, sea was immediately associated to a negative element that brought misfortune.

In addition to the historic phenomenon of dominations, always too hard, banditry that increases and develops exclusively in the inside areas in the 1800s, was characterized, since the birth, by some contingent factors: the abolition of the feudal system with the consequent elimination of the "ademprivio" - namely the common, civic and collective use of a land; use of a land by all the people in a public way – and the Edict of the "chiudende" – the closure of fields. Factors that in these areas generated some pains, revolts and atrocities more than other. The collective management of land was a cornerstone of the Sardinian society. The end of this community system of ancient direction and the demise of feudal system created a devastating hate by Sardinian people. The Government redeemed feuds and it appeared as a very hard collection agent, applying the reform damaging farmers and shepherds.

So it was born the irreconcilable contrast between Government and Sardinia, Continent and Island, City and country, that increased incredibly in the hinterland of the Barbagia, marginalized and excluded from whatever process of development. In these areas it was created an archaic way of resistance. A resistance always present despite almost never unitary and not always messenger of positive values. It had a very solid base: keeping intact the inside status; it had to stay again su connottu, “the known”; they had to persist the same traditional laws intensely well-established.

01 October 2015 Giovanni Corbeddu Salis

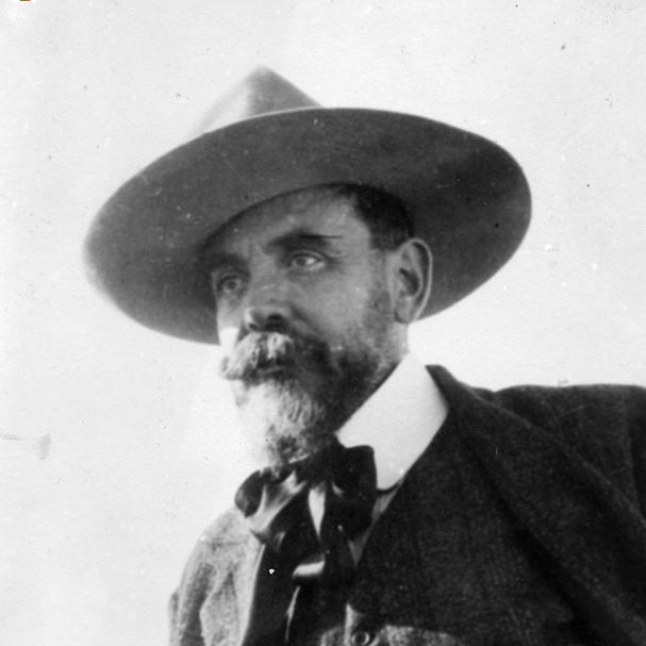

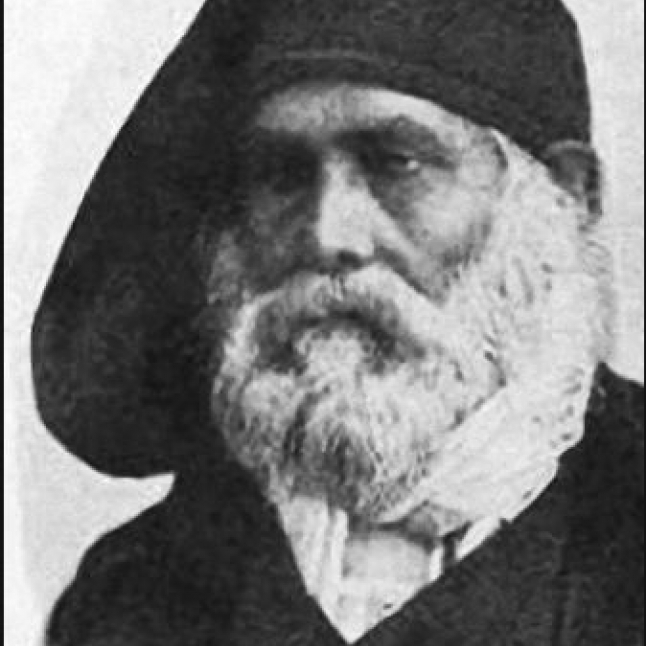

Giovanni Corbeddu Salis was one of the most well-known Sardinian bandits of the end of the 1800s. If we analyzed quickly his criminal curriculum, we would have to condemn, through disgust and bluntly, all this brutality and ferocity. But the “King of escape”, as he was nicknamed by his compatriots, has some features that make him different from the classic notorious bloodthirsty bandit. It is necessary to look deeply. And this is what we will do.

About the bandit Corbeddu they loomed the most varied accusations that included theft, damages, extortions, robberies, aggressiveness and murders. A sentence of death penalty and one of life in prison, a bounty of eight thousand Liras and twelve warrants of arrest.

Corbeddu, born in Oliena in 1844, was one of the most well-known Sardinian outlaws of that epoch. His life was crossed by a tragic choice – that marked unequivocally his destiny – from impressive actions, criminal gestures, pacific and unexpected acts. A state of being in hiding that lasted eighteen years, a cave that has his name, the role of wise man given to him by population during the disputes, that had in the last years of his life and that sense of silent respect that today is aroused inevitably by his figure.

01 October 2015 The big hunt in Morgogliai

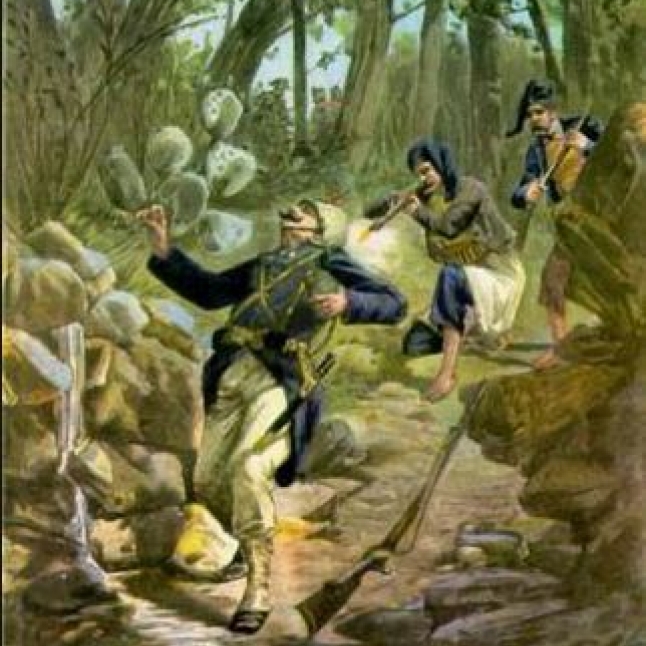

The enduring fight between bandits and security force reached the maximum on ninth and tenth July 1899. Today that dispute is remembered as the “Battle of Morgogliai” and it is considered one of the biggest and the most tragic armed conflicts that happened in Sardinia in the 1800s.

On the one hand, there were the most famous fugitives of that epoch: Elias brothers and Giacomo Serra Sanna from Nuoro, Giuseppe Lovicu from Orgosolo, Tommaso Virdis from Oniferi and Giuseppe Pau from Oliena; cruel bandits that constituted a criminal gang that was respected and dreadful in the whole area of Nuoro; on the other hand, around two hundred Carabinieres and soldiers.

“Proite no los chircas in Murgugliai”? (Why do not you search them in Morgogliai?) It was this sentence, said in a whatever day and declared by one of the many invisible mouths, that proclaimed the end of the dreadful gang of bandits. Because since that moment the everybody’s eyes in an only instant were pointed exactly towards Morgogliai, penetrating into that inaccessible woods, between the territory of Orgosolo and that of Oliena, a place as a shelter, an unassailable outpost, a crucial center of rebellion, a bastion of terror.

Since that moment, they studied a plan for going to drive the criminals out and to restore serenity in the whole area. Serra Sanna brothers and the other bandits were accused of a series of murders such that they made pale; in addition to robberies, thefts, incendiary actions and other brutalities, their incredible cruelty and yearning of revenge aroused clamor. For them there was a big bounty and an infinitive series of condemnations.

01 October 2015 Bastiano Tansu the bandit in love

Love, honor, revenge and blood. It seems that, since the beginning of times, the World rotates around them. Human feelings and passions, told in the farthest past in the epic and chivalric poems, in the modern times in the pages of crime news in the newspapers. We cannot take the feuds, that were all the rage in Sardinia in the Nineteenth and the Twentieth-Centuries, away from the romantic aura that impregnates them; we cannot consider them only as brutal murders, but it is necessary to analyze the passions that animated stories soaked of blood.

What happened in the Northern Sardinia, in Capu de Susu, indicates a situation with some outlines definitely different compared to the Southern Sardinia. We can consider Capu de Susu as a place that includes the whole territory of Nuoro and Sassari up to the confines with the Sea of Corsica, a place that little considered the geographic confines that were imposed and that have always had an administrative and not historical relevance; on the contrary, it felt to be a whole, although each village identified into itself, with the same rules and traditions, very different to those of de Capu e Giossu, in the Southern Sardinia.

Usual rules transmitted orally – the writer Antonio Pigliaru decreed them in twenty-three norms of the Code of Barbagia – that were always considered, by the “Capuesusesus” (the Northeners), binding in a definitely greater way compared to those of the Government. Norms that were provided of intrinsic legality and that were efficient and unique, provided of sacredness and superior than whatever precept, religious too.

01 October 2015 Bandidos II part

What indicated the Sardinian bandit as a bandit? Among the various categories identifiable with banditry one in particular gathered all the Sardinian bandits, namely who that persecuted or not persecuted by a warrant of arrest, grilled or already condemned sentenced for a crime, were removed to justice, escaping.

In the hodgepodge there were lots of them. It is evident as there was the identification of the gang – at least at the beginning. There is only the individual and this is the first consideration. Then, it was important to understand if crime or theft, of which someone was accused, was really committed.

For most of the times, the career of a bandit had its origin from an event that is apparently not arduous and certainly inconsistent. Anger and hate activated by a small spark, then burn up irremediably: the accusation of a theft or of a border violation of cattle, a threat, a tragic mistake, a calumny. The circumstance, the accusation has to be proved, but, in the interim, the suspect activated, in the indicted’s mind, a devastating process that is difficult to give up.

The total lack of faith in the regular justice materializes actually only in the escape and in the state of being in hiding. This is the unequivocal sign of the guilt to which then there will be the revenge. Sometimes that guilt is valid. Sometimes not, there is nothing true, but, by now mechanism was activated. A simple innuendo can mark the fate of a man; it can change forever the process of his life.

01 October 2015 The night of St. Bartholomew

It is in 1899 that Patella, the captain of the Carabinieres of Nuoro, in a restaurant in Oliena, discussed the phenomenon of Barbagian banditry, with the Lieutenant Giulio Bechi, which will become the author of the book "Big Hunting", one of the most characteristic about this argument.

A day of meetings that will mark the memory of the soldier, especially thanks to the fateful encounter with Maria Antonia Serra Sanna, who Bechi remembered as the Queen of the town (sa Reina), feared, obeyed and protected by a "blue wall of silence".

One cannot know what this meeting did arise in the mind of the "mainlander" lieutenant, but made manifest to his captain in a rush the need for a punitive action, convinced of the need that they should intervene immediately and arrest them all: bandits, and not.

In "Big Hunting" the lieutenant reported the occurrence of the capture of the opponents to the "Meritorious" (the Carabinierees Corp), from the other perspective, that of the carabinieres. The one who was considered "colonial" or "invader" in a land already under the rule of a well established social order, although not formal, and, without doubt, alternative to the state law, which was the Barbaricine ordering.

01 October 2015 The poet meets the bandit

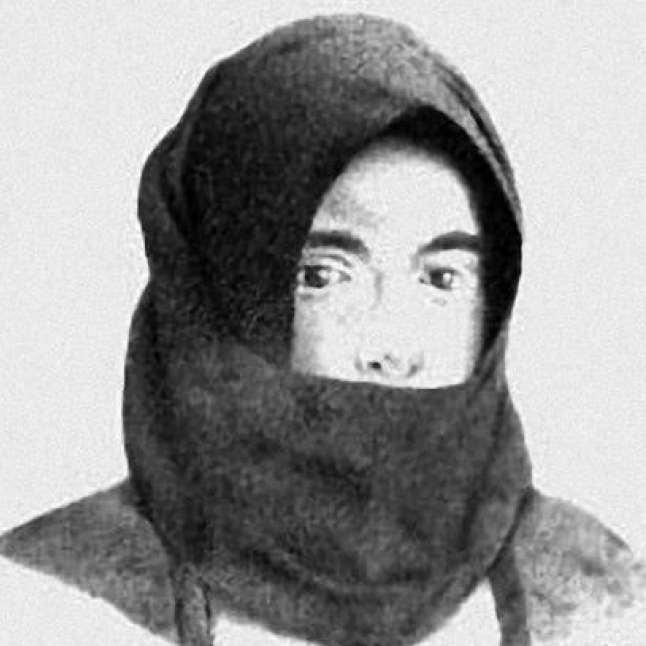

It was the February of 1894 when Sebastiano Satta and his journalism mate, Gastone Chiesi, in the cave-shelter of Setti-Funtani, in the territory of Sassari, interviewed the fugitives Francesco Derosas, nicknamed Cicciu, Luigi Delogu and Pietro Angius, some bandits of Usini (SS).

Letting the bandit speak, for Satta meant also idealizing his rebellion and identifying it inevitably with the social pain and with the anguishes of the rural world, of which we had already appreciated the extraordinary lyricism in “Songs of Barbagia”, through famous and well-known verses addressed exactly to bandits named “beautiful, ferocious and courageous”. The poet Satta is the dignified excellence without equal individuals in Sardinian. His verses are enduring, but, to tell the truth, also this interview is lasting.

Everything began thanks to the meeting between the poet, the journalist and a youngster, with a mysterious attitude, who exhorted them to follow him and then he explained who was the person that wanted to talk with them. He was the notorious bandit Cicciu Derosas. So, it was born the fear but also the desire of becoming the custodians of the confession by a brutal bandit who had spread terror in the area of Sassari, who had in his conscience a dozen of murders, who acted of committing others and who could escape incredibly to the frenzied investigations by the security forces.

They decided to follow that unclear messenger. From the dark lane, they come out in a road open to vehicles; they climbed down a hollow and they walked through a wooded valley; they went beyond a bridge and they walked into the terrible dark of the night. Finally, after a long stroll in the darkest silence, the stock of a rifle shone and it was heard the sound of a trigger. So a gloomy voice burst into: “chie ses”? “Eo” – “Who is”, “It’s me”. And the way was free.

01 October 2015 The legal order of Barbagia

The code of Barbagia has a history rooted in the customs and own used by a population turned into the use of Community lands, after hearing of community ownership ab origine compared to the birth of the Kingdom of Italy.

After the proclamation of the unification of Italy on March 17, 1861, the crucial issue for the government was to manage the destination of the former feudal domains on which burdened the civic uses exerted by the population, comprising the entitlement of grazing, farming and wood gathering.

The abolition of the shared use rights of the territories, which occurred with the law of 1865 that qualifies as a crime against the state property the collective use of the land, marks a profound adversity by the shepherds community to the state law.

The general discontent was already defined among the people with the enactment of the Edict of Enclosures issued by the Viceroy Carlo Felice with the law of 1820, which allowed "any owner to freely close a hedge, or wall, pit, whatever its soil not subjected to easements of pasture, passage, or fountain of water trough".

01 October 2015 Sa Reìna of Nuoro

On the central high ground, a fulcrum of communication between the valleys that stand out as arduous on the ground, Nuoro rises up, the main town of the Island’s culture. The center deserved the epithet of "Sardinian Athens" because of the great cultural ferment that has been spreading here during the last years of the Nineteenth Century until the next, that presents some examples of big artists like Deledda and Satta. But, Nùgoro, will be remembered also as the town of the woman who represented the Sardinian history of the end of the 1800s.

She was called sa Reìna (the queen) for her notorious audacity and her decision power through which she was distinguished among the people of Nuoro, through whose streets she walked wearing elegant clothes embellished with traditional jewels with the precious shining. Maria Antonia Serra Sanna lived in Nuoro between the 1800s and the 1900s and she consecrated her life to support the brotherly will of satisfying the ambitions of economic and social improvement of their own family. Indeed, the Serra Sanna family did not have rich origins.

01 October 2015 Paska Devaddis

“Paska Devaddis was like us, either beautiful or ugly, either lawyer or poet. Paska went up through the death, when she was found and composed in her empty house. The whole village went to see her”. [...] “but she was already a shadow, a face created by the candles that surrounded it”.

This small fragment of dialog is extracted from “Paska Devaddis – Three radiodramas for a theater of Sardinian people”, by Michelangelo Pira. In this way, she was remembered by those voices led by the pen of the big anthropologist of Bitti.

Among the figures of Sardinian bandits, that of Paska Devaddis had a preponderant role. Bandit is a typically masculine figure. Woman, for her nature, unlikely, can become a woman bandit. Too factors and causes, too reasons and irremediably opposing motivations. It is a world dominated by man. Banditry is something "suitable for men". Woman approves, despairs and appears only in the moment of grief. But for Paska it was not such.

30 September 2015 The last Sardinian bandit

It was back in 1848, the year of the so-called "long-awaited reforms", which sees the collapse of the government in view of the absolute stabilizing of a more strict civilization. The difficulties of implementation of such socio-political objective soured increasingly with the massacre of Saba and Careddu families (1850) and that of Saba and Macioccu (1851) up to the cholera outbreak in Sassari in 1855 that caused more than five thousand victims, resulting in attenuation of social disputes moved by political struggles.

It was in this scenario, nothing short of apocalyptic, in the first decade of the constitutional government (1849-1859), that took place the story of the bandit, not for the evil spirit, but because of its determination in rebellion against harassments.

The pride personality, the chivalry generosity, the hatred directed only against spies and enemies as well as the repudiation of theft, outlines the typical Sardinian bandit, the figure now vanished in the Island. According to the writer Enrico Costa the Sardinian bandit "is not a bandit, not a thief, not a robber, not a blackmailer."

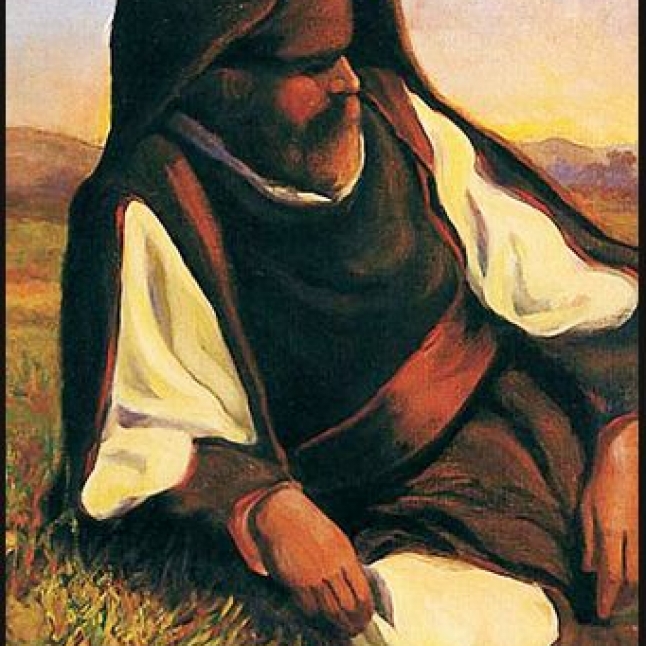

Of virtue and intellectual rectitude are featured those men who are not born vicious, but become so to survive as Giovanni Tolu, considered by the writer the last Sardinian bandit.

01 September 2015 The lands of the bandits without a name

Up there in the mountains some charming villages rise up and they represent the background of numerous legends that state what is the magnificence of Sardinia.

Panorama is unique and the majesty of the mountains is a cover for wonderful landscapes, places for a shelter for the bandits without a name.

The beauty of the granite rock sides and of the holly oaks and oaks woods, into which it is possible to see the first rays of the sun that illuminate the ample and damp land. Silence and serenity are active in these areas crossed by the only noise of the flowing of streams’ waters and by the smell of leaves, mushrooms and mixed berries.